Social Security and Medicare run based on permanent provisions that annually update key tax and spending parameters but without regard to the status of their trust funds. Consequently, as the U.S. population ages and health care costs rise more rapidly than household incomes, both programs are expected to run short of needed resources to pay full benefits. A reform authorizing automatically triggered adjustments to close these widening gaps between spending and revenue would remove insolvency as a persistent threat. The result would be more financial certainty for retirees and stability for the full federal budget.

Despite the immense political and financial payoff from taking this step, most elected officials are likely to oppose it, at least in the current environment. Many Republicans have pledged never to raise taxes, which would become required with automatic solvency adjustments. On the other side, Democrats believe their political fortunes are tethered to their commitment to oppose all benefit cuts, which also would get jettisoned with an automatic mechanism. Violating these long-standing positions is seen as courting electoral annihilation.

For the moment, though, that kind of breakthrough is a long shot as the 2024 election has reinforced opposition to even discussing changes to these programs. But that environment might not last much longer. One or two bad economic or geopolitical breaks could accelerate trust fund depletion and force Congress to confront the problem sooner than it would like to.

If that occurred, relying on automatic stabilization may look more attractive than another round of temporary and fleeting fixes. It also would be fully consistent with the programs’ current designs and political histories.

Off Course

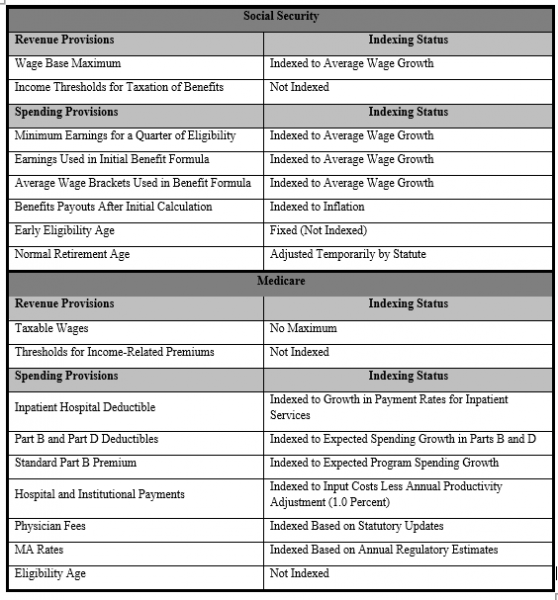

Congress has written into Social Security and Medicare scores of existing annual adjustment criteria (Table 1 provides a summary). While these provisions satisfy certain objectives that policymakers have determined to be important, they do not prevent program revenue and spending from diverging in a destabilizing fashion.

In Social Security, after the initial benefit calculation, monthly payouts are updated annually each January to keep up with consumer inflation. On the revenue side, the upper limit on taxable earnings rises each year with growth in average wages in the national economy. Many other provisions are modified to keep the average replacement rate on covered earnings steady across generations.

Congress wrote these adjustments into permanent Social Security law because without them the natural evolution of the economy would alter the results for beneficiaries. For instance, if Social Security benefits were not indexed to consumer inflation, as they have been since the 1970s, their real value would erode each year. In an earlier era, Congress frequently approved ad hoc benefit increases to prevent such erosion. These interventions pushed program spending above what would have occurred with calibration based on inflation data.

Medicare’s adjustments span key insurance design parameters, including the separate annual deductibles required in parts A, B, and D, and also include modifications to what hospitals and other institutional providers of care are paid for covered services. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) introduced a “productivity adjustment” that lowers the annual inflation increases that hospitals and other providers receive by about 1 percentage point.

These adjustments meet certain congressional priorities but they do not ensure trust fund solvency. In both Social Security and Medicare, the growth in the beneficiary populations is more rapid than it is for the workforce paying taxes. Further, health care cost pressures are also increasing per capita Medicare expenditures above inflation. The result is an expected depletion of all trust fund reserves in Social Security by 2035 and in the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund by 2036.

The problem is actually worse in Medicare than is commonly understood because the program’s other trust fund, for Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI), pushes up federal debt but in a way that is obscured by its design. Currently, SMI receives an annual transfer from the Treasury’s general fund covering 75 percent of total expenditures. These transfers are not backed by a specific tax, which means the Treasury must borrow to meet the obligation.

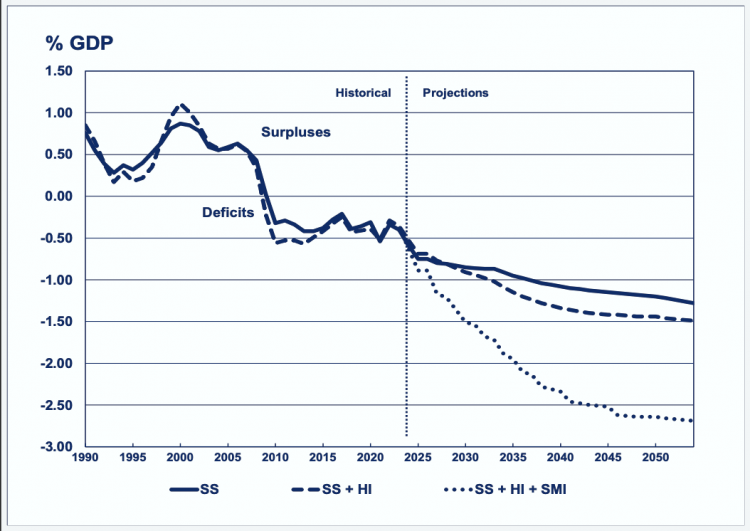

Figure 1 illustrates the severity of the overall challenge. The emerging gaps between revenue and spending within Social Security and Medicare HI are expected to grow from a combined 0.5 percent of GDP annually to 1.5 percent by mid-century. If the annual transfers to SMI were limited in the future to what they are currently (1.6 percent of GDP each year), then the combined deficits in Social Security and Medicare would exceed 2.5 percent of GDP on a yearly basis well before 2050.

Sources: 2024 Social Security and Medicare Trustees Reports

A Two-for-One Deal

The widening gap between revenue and spending associated with Social Security and Medicare is the cause of the trust funds’ depletion and the rapidly escalating borrowing requirements for the government. Under current projections, even though the trust funds will be unable to pay full benefits, the rules for spending forecasts assume full benefits will continue after insolvency, which implies the gap will be covered with higher federal debt. This assumption is a critical reason the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects federal debt will reach historic levels in this decade and then climb to over 150 percent of GDP by mid-century.

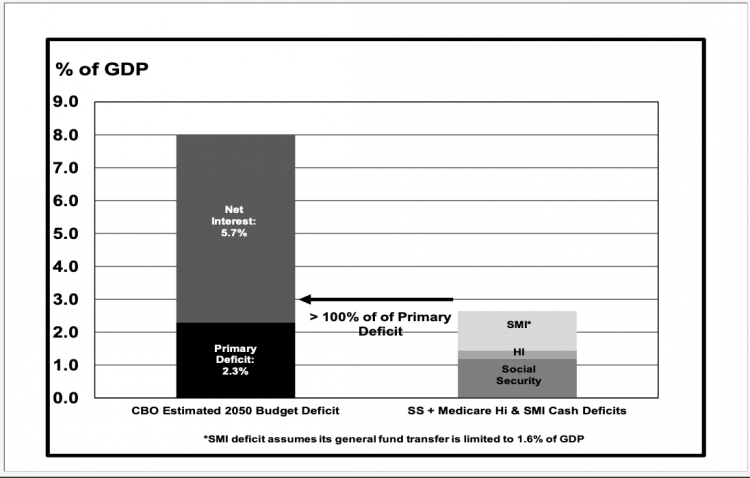

Figure 2 demonstrates the degree of overlap that exists between the financial hole that is expected for Social Security and Medicare and projections pointing to the rapid escalation of federal debt. In 2050, the cash deficits in the major entitlement programs (a measure that excludes the effects of interest costs) are expected to exceed the cash deficit for the entire federal budget. In other words, the rest of the government (excluding Social Security and Medicare) is projected to run a cash surplus in 2050 that will be more than offset by the deficits in the government’s largest domestic programs. Of course, this overlap also signals that a solution for Social Security and Medicare would go some distance toward stabilizing the outlook for the full federal budget.

Options

There is no single right way to build automatic solvency adjustments into Social Security and Medicare. Congress could choose from multiple approaches based on what might attract sufficient support to pass. Several considerations would likely come into play:

- Congress could approve automatic adjustments in lieu of other reforms, or use automatic adjustments to ensure solvency in case other approved reforms fall short of their objectives. In other words, automatic adjustments could be the reform or a backstop to other reforms.

- The available levers for Social Security are more straightforward than they are for Medicare and have been studied extensively. For instance, Congress could adjust the normal retirement age (now scheduled to reach and stay at age 67 in this decade) in tandem with improvements in longevity, or to meet financial targets. Further, it could gradually adjust the rate of return for high-wage earners downward while also bumping up the combined employer-employee payroll tax rate (now 12.4 percent) or the annual wage limit upon which the tax is applied, or possibly both. These adjustments might be phased in whenever the trustees project a shortfall occurring within the first decade of a forecast period.

- In Medicare, Congress could adjust the payroll tax rate, the required monthly premiums for parts B and D, and the deductibles that patients must satisfy before the insurance starts covering bills. Further, it could also lower what hospitals and doctors get paid through across-the-board cuts or other adjustments. The distribution of the financial burden across these potential levers would depend on what could achieve majority support in Congress.

- Congress might choose to place responsibility for implementation of these adjustments within the Social Security Administration and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services based on the forecasts, which are required in the annual trustees reports. The goal should be to minimize disruption to the public by phasing in the changes on a gradual basis over long transition periods. It is instructive that the current phased-in increase in the normal retirement age in Social Security (from 65 to 67) was enacted by Congress more than four decades ago, and is very gradual. The implementation of this change has hardly registered in American political discourse.

Trust Funds With Enforceable Limits

When Congress created Social Security and Medicare, it placed them within trust funds that would track their revenue and spending across decades and generations to ensure fairness and financial stability. These are retirement benefit programs that workers begin earning when they first enter the workforce as teenagers and young adults, so it is critical to have some budgetary mechanism to provide discipline over the long term.

What’s been missing is the conformance of program rules with the limits implied by trust fund accounting. Currently, official projections assume the government will borrow as needed to cover the deficits that are expected in these programs, even though the trust funds prohibit such spending. The vagueness that exists today around what would be done to keep spending in line with revenue leads many observers to assume Congress will prefer a bailout to the most likely alternative, which is indiscriminate spending cuts to prevent full depletion of reserves.

The solution is to provide these trust funds, which are devices the public has come to expect and support, with real teeth to prevent borrowing as the solution. If forecasts continue to show fast-approaching deficits and insolvency, it makes much more sense to implement steady and gradual adjustments to the major programmatic levers to keep the programs solvent and sustainable on a permanent basis.

Indeed, this solution is so sensible it seems almost inevitable. These are long-term programs that Congress cannot be expected to modify on a frequent basis. They have to be run based on formulas and annual adjustments. The only question is whether the purpose of these adjustments will be expanded to serve solvency in addition to their current long list of objectives.

James C. Capretta is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He is the author of “Automatic Solvency Adjustments in Medicare: Conceptual Considerations,” published by AEI in September.